Reviews – You Are Here by Award Winning Author Cynthia Flood

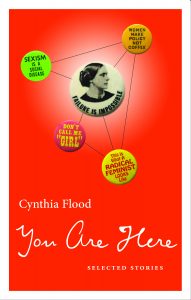

You Are Here: Selected Stories by Cynthia Flood, with an introduction by Rebecca Rosenblum

1634 Shades of empire and activism

You Are Here: Selected Stories

by Cynthia Flood, with an introduction by Rebecca Rosenblum

Windsor, ON: Biblioasis, 2022

$26.95 / 9781771963411

Reviewed by Ginny Ratsoy

Read the full review at thebcreview.ca

Emma Donoghue has observed, “The great thing about a short story is that it doesn’t have to trawl through someone’s whole life; it can come in glancingly from the side.” These words speak to the brevity inherent in the genre. They could also apply to narrative stance; more of the stories in this collection feature either a third-person or a first-person narrator who is outside the main focus of the plot than not. Curated from a body of work published over a 35-year period, You are Here presents insightful, often incisive, glances into fictional lives. Whether her subject is a young woman, an old man, or the more-than-human, whether her setting is mid- 20th century London or Toronto or 21st-Century Vancouver, Cynthia Flood employs a realistic style to glances into characters who are products of their respective time and place, while at the same time surprising, sometimes jarring, us with unpredictability.

Cynthia Flood at Shawnigan Lake

Two stories about youth speak to Flood’s range. In “Calm,” a dreamer, recently moved to Vancouver and chastised by his mother and her latest man for sneaking out at night, repeats his transgression. Taking inspiration from the Resist! posters he encounters, and four mounted police he follows as he explores both seedy and privileged neighbourhoods, the boy enters the dark Lagoon area, where the delight of the horses as they wade in the ocean transfixes him. After returning home and again incurring wrath, he lies in bed contemplating transcending his circumstances, and taking his cue from the horses, chooses patience meantime. One of the most evocative stories in the collection, “Imperatives,” also explores an alienated child in a style and with an effect reminiscent of Alice Munro’s work. Out of her element in a new city (Toronto, mid-20th Century, early winter) and school — complete with stern nuns and confounding rules — Nicola abides her newborn brother’s incessant crying and her mother’ slow recuperation from childbirth. However, when she has lost yet another fountain pen, after her parents’ warning that they would not replace it, she skips school, fearing the consequences of being pen-less, and escapes to a park, where she soon befriends a strange man of blurry background and motives. While authorities take two days to report Nicola’s absence, the two explore the city. All the while, the reader grows increasingly uneasy about the stranger’s intentions. The story vividly evokes a time when roles and rules were more rigid — for better and for worse. “Imperatives,” both quotidian and edgy, as it powerfully conveys the loneliness of the outsider and the vagaries of communication, is a salient reminder to adult readers that the fears and anxieties of a child, although they may seem trivial, are profound.

Flood, My Father Took a Cake to France (Talonbooks, 1992)

Flood’s depictions of provincialism brought to mind Rosemary Sullivan’s description of mid-20th Century Toronto (in Margaret Atwood: Starting Out) as “still frozen in the permafrost of colonialism” (p. 98) — a perfect descriptor of the protagonist of Flood’s My Father Took a Cake to France. A narrator re-imagines a story once told to her. Her 26-year old father, a Canadian scholar attending Oxford, suffers from both a snobbery due to his scholarly prowess and a sharp colonial mentality, having internalized a view of empire and (woefully inferior) colony that will dog him forever. The setting is an English bakery, where a comely young woman whom he finds at once attractive and inferior him serves him. The narrator imagines the scene meticulously, down to the shopgirl’s cataloguing the names of all of the cakes the bakery features. The picture of the father is consistently unflattering, as he lusts for the shop girl while purchasing a cake for his bride. When the cost of his selection is almost prohibitive, he sheds angry tears, feeling a “freezing resentment that the world refuses to order itself as it ought” (p. 81). With a fast forward to his middle and old age, including his last days, the daughter portrays him as unwavering, bigoted, and sexist, and, ultimately, crushed by his inability to transcend his Canadian roots and receive the recognition duly his. Images of the wife are few and fleeting: lovely, strong, and accomplished as a bride in Paris, she is long suffering and doting in the relationship a half-century later. The portrait of the father is memorable for its pathos: for the effects on those around him of a petty, unhappy man paralyzed by societal strictures.

King George VI with Princess Elizabeth, 1946

Another strong story depicting the British-colonial relationship is “Early in the Morning.” Narrator Amanda, as a Canadian in a British boarding school for girls, is an outsider, a “minor planet” (p. 112). The death of George VI highlights the depth of the monarchy’s power in the school as it casts outsiders into light. As time passes, requisite games of cricket, along with charitable needlework projects, resume. Amanda eventually befriends other outsiders, Kay from India and gangly Helen. The three gleefully plant seeds in the kitchen garden and imagine ways to commemorate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. However, reality again intrudes when the headmistress announces Kay, having contracted polio, is in an iron lung. Helen and Amanda grow closer as their garden grows and they prepare a coronation speech, suspecting they will be a duo, rather than a trio like the other groups. At church, Kay’s death is announced. The duo is shunned by the other girls until after the funeral, about which the two know nothing. They perform their own private farewell, dedicating the garden to Kay — a bittersweet ending well executed.

A suite of stories deals — centrally or peripherally — with activism. “Two Score and Five” juxtaposes the lives of two university friends over two decades. Mary narrates more about Marjorie’s life than her own. Marjorie becomes involved with a painter, a professor, and a doctor in succession, her own writing and painting talents subsumed in caring for others, to Mary’s chagrin. Meanwhile, Mary rises through the library ranks, travels to Bermuda annually, and, upon experiencing the glass ceiling in the library world, joins a feminist collective. When Marjorie’s third relationship breaks up, she returns to Vancouver from Toronto for an operation. While visiting Marjorie in hospital, Mary relates, second-hand, a complicated lesbian love triangle at the collective. Marjorie, unfamiliar with the characters per se, successfully predicts each plot twist through her own lived experience in love affairs. Their conversation culminates in truth-telling: Marjorie does not see herself as a foiled artist, as Mary has, but as a very minor talent who has lived a full life through those relationships. She begs Mary to make advances to men. Tension turns to humour as the two now regard themselves as “two middle-aged women friends gazing at the mystery of the other’s life” (p. 58). This is a quiet, witty study of, at once, the significance of lasting friendship and the inscrutability of that relationship.

“Blue Clouds” and “Dirty Work” are harsher, jottier stories about activism, each narrated by those on the sidelines of the movement, focusing on seamy power dynamics; infighting and sexual indiscretion feature prominently. “A Young Girl-Typist Ran to Smolny: Notes for a Film,” replete with footnotes, juxtaposes two stories and plays with different levels of reality. As young radical Kate goes door-to-door to sell subscriptions to a leftie publication, she daydreams about the typist who ran to Smolny with a crucial message for Trotsky. Knowing little about the event, she romanticizes it, imagining it as a film. The outer story, of Kate’s rite of passage into the organization, is also in film script form — a sketchy style, heavy on visuals. After several briefer interactions, Kate enters the home of Mac, who provides a history of the local movement through his lived experience, starting with the Second World War and culminating in the early 1960s when he had a mill accident and got no union support and paltry compensation. Mac shares much about infighting and corruption in the movement before he pays for his subscription to the Voice of the Revolution, but Kate seems unscathed as she goes on her merry way to complete her assignment — but not before the film directions point to a photo of her as an old woman. Although this is the most overtly experimental of the stories, it is not atypical of Flood’s work in the complexity of its narrative style. Flood’s fictionalizing of her own activist experiences is a valuable — if unsettling — glimpse into events not often chronicled.

This review itself provides only a glimpse into the 21 stories in You are Here. The book’s title, by the way, is not the title of a single story. Whether or not it is a sly allusion to two famous questions Northrop Frye juxtaposed in The Bush Garden, You are Here is a crisp and positive label for a collection that, as Rebecca Rosenblum, who wrote the book’s introduction, notes, illustrates Flood’s ability to re-imagine recurrent themes. Into her glances into the seemingly ordinary, Cynthia Flood injects much complexity and depth.

*

Ginny Ratsoy is Professor Emerita at Thompson Rivers University. Her scholarly publications focus on Canadian fiction, theatre, small cities, third-age learning, and the scholarship of teaching and learning. In addition to counteracting ageism by maintaining a growth mindset through freelance writing and community engagement, she promotes later-life learning through her involvement as a board member, instructor, and coordinator for the Kamloops Adult Learners Society. Her upcoming course for KALS looks at several generations of female Canadian short story writers. Editor’s note: Ginny Ratsoy has recently reviewed books by Reed Stirling, Maria Tippett, Gillian Ranson, Jo Owens, Iona Whishaw, and Mark Bulgutch for The British Columbia Review.

*

Rebecca Rosenblum wrote the introduction to You Are Here

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.